The

Rastafari movement, which began in Jamaica during the 1930s, has become internationally

known for its contribution to culture and the arts, as well as for its focus on

peace and “ital” living. Major icons include reggae musicians Bob Marley, Peter

Tosh, Bunny Wailer and Burning Spear, with the movement overall projecting a very

male image.

But women have

contributed significantly to the development of Rastafari, as Jamaican-born historian

Daive Dunkley has shown through his research. Rastafari women were

particularly active in the resistance against colonial rule in the first half

of the 1900s, and they created educational institutions for young people and helped

to expand the arts sphere in the Caribbean, among other work.

These

contributions are highlighted in Dunkley’s latest book, Women and Resistance

in the Early Rastafari Movement, an essential addition to the history of

Rastafari - which scholars generally see as both a religious and social

movement. US-based Dunkley, an associate professor in the University of

Missouri’s Department of Black Studies and director of Peace Studies, spoke to

SWAN about his research, in an interview conducted by email and videoconference.

SWAN: What inspired your research on women’s role in the

early Rastafari movement?

Daive Dunkley: There is a story here. My inspiration

for writing about women’s role in the early Rastafari developed from research I

had been doing since 2009 on Leonard Howell, one of the four known founders of

the movement. I quickly realized that women were a significant force in the

group that became known as the Howellites and were critical to all their

considerable initiatives. These included developing the first self-sufficient

Rastafari community, known as Pinnacle.

Hundreds

of women joined the estimated 700 people of the Pinnacle community in 1940,

located in the hills of St. Catherine, Jamaica. I realized too that the women

had been part of establishing the Ethiopian Salvation Society (ESS) in 1937 and

were members of its governing board. They were secretaries and decisionmakers,

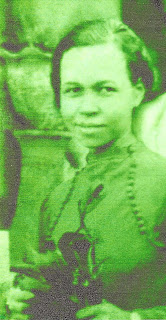

including Tenet Bent, who married Howell. Bent was one of its leaders and

financial backers. She also had connections in middle-class Jamaica that proved

critical to the development of the ESS as a benevolent Rastafari organization.

Interestingly

the ESS created a constitution written chiefly by women who called it a “Christian

charity.” And some of its first outreach programs were also clearly determined

by women, such as providing relief in the form of food and clothing to

survivors of natural disasters in several parts of Jamaica in the late 1930s. In

2014, I decided to focus my research on the activities of the early women, who

came predominantly from the peasantry. The colonial government and newspapers

largely ignored the activism and leadership of these women in the development

of the Rastafari movement.

SWAN: Were you surprised by the information you discovered?

D.D.: I

was not surprised by my information about women’s political, economic, and

cultural activism within the early Rastafari movement. My earlier research on

the antislavery activities of enslaved people included research on women. Despite

slavery, these women remained active in the resistance - undermining, escaping,

or abolishing slavery altogether. I found out that women’s role in the early Rastafari

encountered silencing by the colonial system. We helped maintain this silencing

in later writing about the early movement. What I read in terms of secondary

scholarship was largely androcentric. I learned the names of the four known

founders and some other prominent men. They engaged the colonial system unapologetically

as Rastafari leaders. I read nothing similar about women, which I found pretty

strange.

Moreover,

when women were portrayed, including by British author Sheila Kitzinger in the

1960s, it was essentially to reflect on how marginal they were in the movement.

By the way, for me, the early Rastafari movement dates from the 1930s to the

end of the 1960s. Women in the 1960s were members of the early action, and many

joined from the 1930s through the 1950s. In other words, early women were

members of Rastafari during and after the colonial system. This system was far

more devastating in its attitudes towards Rastafari than the early postcolonial

government of Jamaica that took over with the island’s political independence

in 1962.

Rastafari

obtained a male-dominated image from the mid to late 1950s with devastating consequences

for all the movement’s women. The colonial system successfully imposed a veil

of silence on women, resulting in our ignorance of these women. More research using

interviews with and about women and closer reading of the colonial archives,

including the newspapers, helped me uncover some of the hidden histories of the

women in the early movement. I was inspired to continue searching for these

stories because I knew that Black women were never silent in the previous history

of the Caribbean or before the genesis of Rastafari in 1932.

SWAN: What was the most striking aspect of this story?

D.D.: This

question is a difficult one to answer because all these stories involving women

were fascinating or striking. But if I were to venture an answer to the

question, I would say that the story about the women who petitioned the

government for fairness and justice in 1934 stands tall among the most striking.

I’ve written elsewhere about this story in a blog for the

book published by LSU Press. I said that the women who petitioned the

government for justice and fairness showed their awareness of the power of

petitions in the history of the Black freedom struggle in Jamaica and the

Caribbean.

These women organized themselves to defy the colonial police,

justices of the peace, and resident magistrate. These entities had dedicated themselves

to silencing Rastafari women and men. The women submitted their petitions to

the central government. They did so in a coordinated fashion to ensure that the

colonial officials did not ignore the pleas.

You

will have to read the book to get a fuller sense of what happened due to these

petitions. I will say that engaging with the government showed an effort not to

escape from the society but rather to transform colonial Jamaica into a just

and fair society. The women wanted the island’s Black people to see themselves

improving. They wanted Jamaica to reflect their aspirations. The activities

aimed at accomplishing this wish were among the most significant contributions

of early Rastafari women. They were not escapists. They were radical

transformationalists if we want a fancy term.

SWAN: How important is this particular segment of history

to Jamaica and the world, given the international contributions of the

Rastafari movement?

D.D.: Rastafari’s

early history is critical to understanding both the history of Jamaica and the

African diaspora at the time. People like to think of the internationalization

of the Rastafari movement as starting from the 1960s and growing from there.

However, my research on early Rastafari women has confirmed that this is not

true. Rastafari was formulated with an international perspective and

established ongoing connections with the global Black freedom struggle from its

very beginning. The women also helped establish relations with Ethiopia on a

political level that included fundraising, organizing, and participating in protests

against fascist Italy’s aggression and subsequent occupation of Ethiopia in

1936-1941.

In addition,

women protected the Rastafari’s historic theocratic interpretations of the

coronation of Emperor Haile Selassie I and Empress Menen Asfaw in 1930. The

coronation event was critical to inspiring the genesis of the Rastafari

movement. Women such as the previously mentioned Tenet Bent maintained the

correspondence with the International African Service Bureau (IASB) through one

of its founders, George Padmore, the Trinidadian Marxist based in London. The

women knew that the organization evolved out of the International African

Friends of Abyssinia formed in London in 1935 to organize resistance against

Italy’s attempts to colonize Ethiopia.

In 1937,

Padmore created the IASB with help from other Pan-Africanists from the

Caribbean and worldwide, including CLR James, Amy Ashwood Garvey, ITA

Wallace-Johnson, TR Makonnen, Jomo Kenyatta, and Chris Braithwaite, the

Barbadian labor leader. The early Rastafari women preserved the history of

Rastafari’s attempts to engage with the global Garvey movement from 1933,

though disappointed by Garvey’s unwillingness to meet with Rastafari founder

Leonard Howell.

Women,

however, helped preserve the movement’s links to Garvey’s Back nationalist

ideology to maintain the Pan-African political consciousness of the African diaspora.

Women also read and discussed the literature of Pan-Africanist women writers

such as Amy Bailey. The newspapers of Sylvia Pankhurst, the British socialist

and suffragist, also kept the early Rastafari women abreast of developmental

initiatives in Ethiopia.

Undoubtedly,

the 1960s onwards brought further development of this international focus,

especially with the development of Reggae and primarily through the touring by Bob

Marley and the Wailers in the 1970s. However, much of the success of Reggae was

due to its Rastafari consciousness developed in the 1930s. This consciousness

centered on the African origins of humans and empowered Reggae with a message

of morality, peace, and justice that appealed to people worldwide.

SWAN: From a gender standpoint, how significant would you

say the research is for Jamaica, the Caribbean?

D.D.: The

early history of Rastafari women revealed some crucial developments in the

story of gender and its dynamics in the modern history of the African diaspora.

The early women challenged gender disparity inside and outside the movement

from the 1930s’ inception of Rastafari. Many of these women had been part of

empowered women congregations in the traditional churches, namely the Baptist church.

Still, they felt that Rastafari focused more on their African ancestry and

therefore was more relevant to their social uplift. Among the gender

discussions initiated by women was equality between the emperor and empress of

Ethiopia, whereas men saw the emperor as the returned Messiah. The women

proposed that the empress and emperor were equal and constituted the messianic message

of the coronation event in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in 1930.

Women

also ensured that they participated in preaching the Rastafari doctrine on the

streets of Jamaica from the early 1930s. They defended men arrested and tried

for their involvement in Rastafari. Many women also ended up imprisoned for

their defense of the movement and its use of cannabis. Women were present

during the court proceedings as witnesses and supporters. Their willingness to

engage the justice system revealed to colonial officials that the male focus in

suppressing Rastafari would continue to fail unless they paid attention to

women.

The

women carried on the Pinnacle community in the 1930s through 1950s when the

police arrested the men. As my book discusses, women were at the center of

initiating the most significant Rastafari organization of the late 1950s, the

African Reform Church of God in Christ. One of its two founders was Edna E. Fisher.

She was prosecuted for treason-felony and did not attempt during the trial to

hide the fact that she was the owner of the land on which they built their organization.

Fisher considered herself the brigadier of the movement. However, scholars have

named the events and the trial after her partner and future husband, Claudius

Henry. Still, Fisher was instrumental in the leadership and creating the

organization’s cultural and political objectives.

SWAN: Why did the Rastafari movement become so

male-oriented in later decades?

D.D.: My

research has shown that Rastafari became male-oriented mainly in the 1950s.

This change was primarily a response to the attempts of the colonial regime to suppress

the movement. Its male leaders and many male followers decided they needed “male

supremacy” to fight “white supremacy.” Scholarship on the Black freedom

struggle in the United States has also disclosed this decision. Despite this

reorientation towards male centrism, women continued to play pivotal roles inside

and outside leadership positions.

Initially,

it made sense for many women to capitalize on the image of male power to protect

the movement because of the targeting of male members by the government.

However,

state officials eventually recognized that targeting men could not end Rastafari.

They needed to take a gender-equitable approach to suppress the movement. That recognition

would lead to the detention of many women by the police on charges of

disorderly conduct, showing animosity towards state officials, such as police

and judges.

Of

course, many women also faced cannabis charges. The male orientation of the

movement continued into the independence period of Jamaica primarily due to the

men seeking to consolidate power. Many cultural and philosophical attitudes

developed around this male-centered identity that started in the 1950s. The male

focus continues within the movement despite women challenging these attitudes

using notions of gender equality inherited from earlier women.

SWAN: How did the book come about?

D.D.: I

started to write chapters for the book in 2014 and revised them over the next seven

years. One of the strategies I used was to return to some of the women and men

I interviewed to ensure that the information was consistent with what they had

told me previously. I also expanded the archival research to include Great

Britain and the United States materials. Regarding research materials for the

book’s writing, the most important sources were the Jamaica Archives, the

British Archives, the Smithsonian, and the newspapers, particularly Jamaica’s Daily

Gleaner.

SWAN: What do you hope readers will take away from it

overall?

D.D.: One

of the things I hope will happen with this book is that it stimulates further

research into women’s role in founding the Rastafari movement. That part of the

history needs analysis that I think will expand our understanding of how Rastafari

came about and give a complete picture of the critical figures in founding this

movement. I believe women were vital to both the genesis and initial

development of Rastafari, who had been articulating its consciousness before the

1930 coronation of the empress and emperor of Ethiopia.

It

is clear from my research that women read the same materials men read and gradually

developed their ideas about Rastafari consciousness independently of men. I

also hope the book will inspire people to see poor Black women as agents of historical,

social changes in the history of the African diaspora. These women had

meaningful conversations regarding materializing social change for the greater

good. I’m hoping readers see these women as intellectual catalysts and

activists who helped shape the evolution of the modern African diaspora. These

women were critical to the decolonization process, for example. – AM / SWAN

Women and Resistance in the Early Rastafari Movement is published

by Louisiana State University Press.

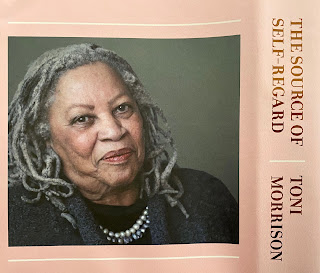

Photos (top to bottom): Dr Daive Dunkley (courtesy of the University of Missouri); the cover of Dunkley's book (courtesy of LSU Press); Tenet Bent (courtesy of Month Howell); Bob Marley - Songs of Freedom; an image from one of Dunkley's scholarly presentations; artwork from the reggae CD Inna de Yard.

Follow SWAN on Twitter @mckenzie_ale.