By Dimitri Keramitas

George Lamming was a pioneer of Caribbean literature whose reputation spanned the Atlantic. He was part of a legendary generation of writers, including VS Naipaul and Derek Walcott, who left what were then still colonies to make careers in London, the capital of the then-regnant British Empire.

Upheaval in his homeland’s region came in the form of World War II. A largely unknown part of the war was the Battle of the Caribbean – a crucial transit point for supplies moving from the port of New Orleans to Europe and beyond. In addition, Trinidad was home to the second-largest oil refinery in the Empire.

The Caribbean became a target of German U-Boats that decimated commercial shipping. The Allies hunted down the submarines, created large bases on the islands, helped Gaullist Résistants overthrow the Vichy regime in the French Antilles. But there was a negative impact as well. Naipaul detailed how American money flowing into their bases resulted in corruption, prostitution and the black market. Lamming, in his great novel, In the Castle of My Skin, described how the fictional San Cristobal, based on Barbados, was deforested for timber and had its rail lines ripped out to provide steel for Britain’s war effort.

To a great extent, Britain’s efforts managing decolonization had to do with the very different war that followed: the Cold War. Just as the US plotted against a democratic leader in Guatemala, invaded the Dominican Republic, and supported anti-Castro Cubans, Britain intervened in British Guyana to quash the democratically elected, but Marxist-leaning, Cheddi Jagan government.

As part of the Cold War effort, Caribbean students were groomed with scholarships (courtesy of the Colonial Office) to Oxbridge and jobs at the BBC Colonial Service. This is where Lamming, Naipaul and Walcott found employment in 1950s London.

Lamming and Naipaul were colleagues at the BBC, but eventually became rivals. In the Castle of My Skin has a serious tone throughout, lyrical language, and a sensitive appreciation of character. Billed as a novel, it is in fact an innovative hybrid, fusing novel, short-stories, and memoir. In contrast, Naipaul’s early works, such as Miguel Street, are admired today for their idiosyncratic style and mimicry of Creole speech, but they were originally seen as bitingly comic, in the manner of Evelyn Waugh. Many West Indians were not amused, and Lamming called Naipaul’s approach “castrated satire”. Ironically, both Lamming’s novel and Naipaul’s Miguel Street resembled one another in their employment of microcosmic settings and young autobiographical personae trying to make sense of their world.

It wasn’t an auspicious time for the traditional English novel. Neither Lamming nor Naipaul would write major fiction during the decade. Instead, they both turned to nonfiction to examine the alienation and destabilization stemming from de-colonization.

Naipaul wrote The Middle Passage, a work of reportage on the contemporary Caribbean. He wrote it after being invited by the president of Trinidad to visit and write on the region; Lamming (who’d spent much of his early life teaching in Trinidad) received the same invitation.

Instead of reportage, Lamming in The Pleasures of Exile turned to literary and cultural criticism to trenchantly express how Western culture, including its canonical literature, distorted the image (and implicitly, self-image) of colonized peoples. In this he was a precursor of critic-scholars such as Edward Saïd, who explored similar themes in his classic Orientalism. Lamming followed that up with two more essay collections: Coming, Coming Home: Conversations II – Western Education and the Caribbean Intellectual and Sovereignty of the Imagination: Conversations III – Language and the Politics of Ethnicity. Lamming also wrote five more novels, notably The Emigrants (1954), a sequel to In the Castle of My Skin.

At that time he was a genial middle-aged man, nattily dressed with a halo of white hair. His double-focus was evident in the classes he taught. As a creative-writing instructor, he was kindly and supportive, even indulgent. He was amused by one of my stories, which satirised then-vice president George Bush. He was more rigorous when it came to his survey of post-colonial literature.

There’d been a violent military takeover in Liberia then, and Lamming turned a cold eye on what was transpiring there. His objective appraisal of the violence recalled Frantz Fanon, and evoked a favorite image of Lamming’s, that of Caliban in The Tempest. In effect he appropriated Shakespeare’s play about shipwrecked whites on an island (perhaps based on Bermuda) and reversed the perspective to that of the repressed indigenous whose rage must ultimately find release. Likewise, his takes on African writers Chinua Achebe and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o gave a 180° spin on the Africa-set fictions of European authors, in particular Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.

Derek Walcott and VS Naipaul both won the Nobel Prize, a distinction which eluded Lamming. Naipaul was eventually made a lord, and lived like a country squire in Wiltshire, in England (however, his plush country abode was rented, not owned). As for Lamming, he returned to Barbados, where he became an elder statesman of literature, and was made a Companion of Honour of his native country.

To many, the most famous Barbadian is no doubt the singer and cosmetics mogul Rihanna. However, George Lamming was probably gratified that in the passage of time he not only reached the ripe age of 94, but also lived long enough to see Barbados become a republic. - SWAN

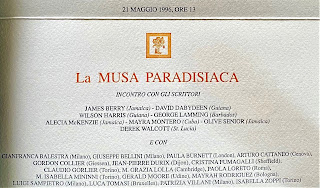

Photos (top to bottom): portrait from In the Castle of My Skin, and book cover (University of Michigan Press); image from the 1996 Caribana literary conference in Milan, and programme of a conference event where Derek Walcott also participated.