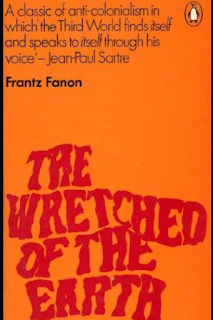

Writers and scholars such as Franz Fanon have examined the effects

of colonialism on the mental health and well-being of both colonized and

colonizer, and the topic is growing in importance in the so-called postcolonial

world.

|

| Frantz Fanon's seminal book. |

During a conference on the issue at the University of Leeds

in June, many scholars also took a closer look at neocolonial structures within

the global health system.

Sanjoy Bhattacharya, a professor in the history of

medicine, explored how the World Health Organization (WHO) claims successes for

itself - such as the defeat of smallpox. Here, he sees a Eurocentric power

structures at work as, according to his research, the dominating narrative is

that diseases stop when the WHO steps in. But this picture is highly

problematic because it ignores the efforts and contributions of developing

countries themselves, he said.

Deepika Bahri, a professor of English, discussed the aim of

colonial powers to “build a reformed class of persons in India”. In the past,

this was in keeping with the objective to “educate the body” of the colonised –

a phenomenon she calls “Biocolonialism”. Nowadays these attitudes still come

into play, especially when one looks at the global marketplace where the main

target of multinationals is to have consumers who behave the same, buying

similar products.

In addition, Bahri addressed the problem of how corporal

expressions and movements are associated with intelligence or are perceived as

a sign of an uncivilised lifestyle, such as whether one sits on the ground or

on a chair. The choice has nothing to do with one’s intelligence, but such

associations work on a subconscious level, leading to certain prejudices, she

said. In one noted example, famous personality Oprah Winfrey in 2012 made the

following comment to a wealthy Indian family on her show “The next chapter”: “I

heard some people in India eat with their hands still.”

|

| A conference text about the issues. |

Scholars also discussed the traumas caused by colonial

oppression in spaces such as residential schools in Canada and Australia, and

they addressed sexual health, women’s health and current developments in

“postcolonial” countries.

Cultural psychologist Tarek Younis, for instance, focused

on the UK government’s “PREVENT” policies which seeks to identify individuals

who are prone to radicalisation, thus obliging health professionals to report

persons for potential crimes. According to Younis’ research, these policies

have racial implications and create a scenario close to the speculative fiction

of Philip K. Dick’s short story “Minority Report”.

Prior to the conference, Leeds University’s School of Earth

and Environment hosted a workshop on research in indigenous contexts, with a

keynote lecture. Métis presenter Zoe Todd highlighted the fact that minorities’

outrage at injustice is often regarded as overreaction - for example,

concerning missing and murdered Indigenous girls and women in Canada. She

stated that according to official reports published in June 2019, such incidents

are now rated as genocide, indicating that Native peoples did not overreact to

these “uncomfortable histories”.

Todd said that another “unhealthy” reality for research

itself is that in US academia, 94% of the hired anthropologists come from only

15 American universities. Thus, a wide range of perspectives is still being

ignored, and academia itself is driven by a few dominating institutions.

Regarding literature,

the conference spotlighted new or upcoming publications that mix humanities

with perspectives on human health and psychological and medical research. Such

publications include Humiliation: Mental Health and Public Shame by

Marit F. Svindseth and Paul Crawford (May 2019), Mad Muse: The Mental

Illness in a Writer’s Life and Work by Jeffrey Berman (Sep 2019), and the

volume on Literature, Medicine, Health from the Moving Worlds

series (Number 2/2019).